Received: Tue 22, Jul 2025

Accepted: Sat 16, Aug 2025

Abstract

Introduction: Cervical disc arthroplasty (CDA) is a motion-preserving alternative to anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, indicated for radiculopathy and myelopathy. We present a rare case of prosthesis migration. Case Presentation: A 41-year-old woman developed progressive weakness and gait disturbance 5 years post-CDA. Imaging revealed prosthesis migration compressing the spinal cord. The prosthesis was removed, and stabilization performed. Discussion: Prosthesis migration is a serious complication influenced by implant design and osteointegration. Timely surgical intervention led to full neurological recovery. Conclusion: Early recognition and management of CDA complications are crucial to avoid severe outcomes.

Keywords

Cervical disc arthroplasty, prosthesis migration, spinal cord compression, case report

1. Introduction

Cervical disc arthroplasty (CDA) is a motion-sparing surgical alternative to anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, often indicated for cervical radiculopathy and myelopathy in younger patients. This procedure aims to preserve intervertebral mobility while minimizing the risk of adjacent segment degeneration. However, complications such as implant migration, fracture, or failure of osseous integration have been reported in the literature, raising concerns about its long-term efficacy and safety [1-12].

This case report discusses a rare instance of cervical prosthesis migration into the spinal canal, emphasizing the clinical presentation, imaging findings, surgical intervention, and postoperative outcomes. The report aims to highlight the possibility of such a complication and importance of timely diagnosis.

2. Case Presentation

A 41-year-old female presented with progressive weakness in the right upper and lower extremities and impaired gait. The patient’s medical history revealed anterior cervical discectomy and prosthesis implantation at the C5-6 level five years prior. Symptoms began with numbness in both arms a year earlier, evolving into significant weakness and balance issues over the past month.

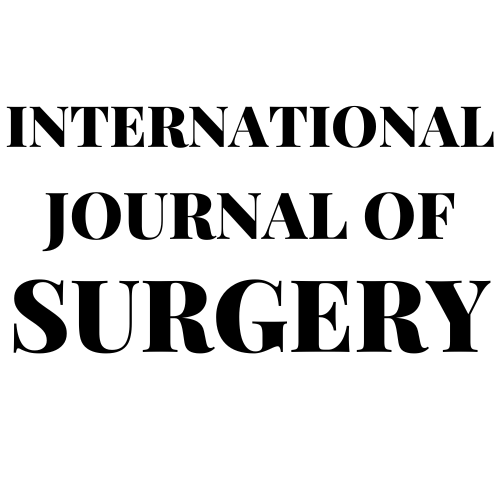

On physical examination, the patient exhibited muscle strength graded 4/5 in the right upper and lower extremities, ataxic gait, a positive Hoffman’s sign on the right, and hyperactive deep tendon reflexes in all extremities. Imaging studies with cervical CT and MRI revealed a migrated cervical prosthesis occupying more than half of the spinal canal, causing spinal cord compression (Figure 1).

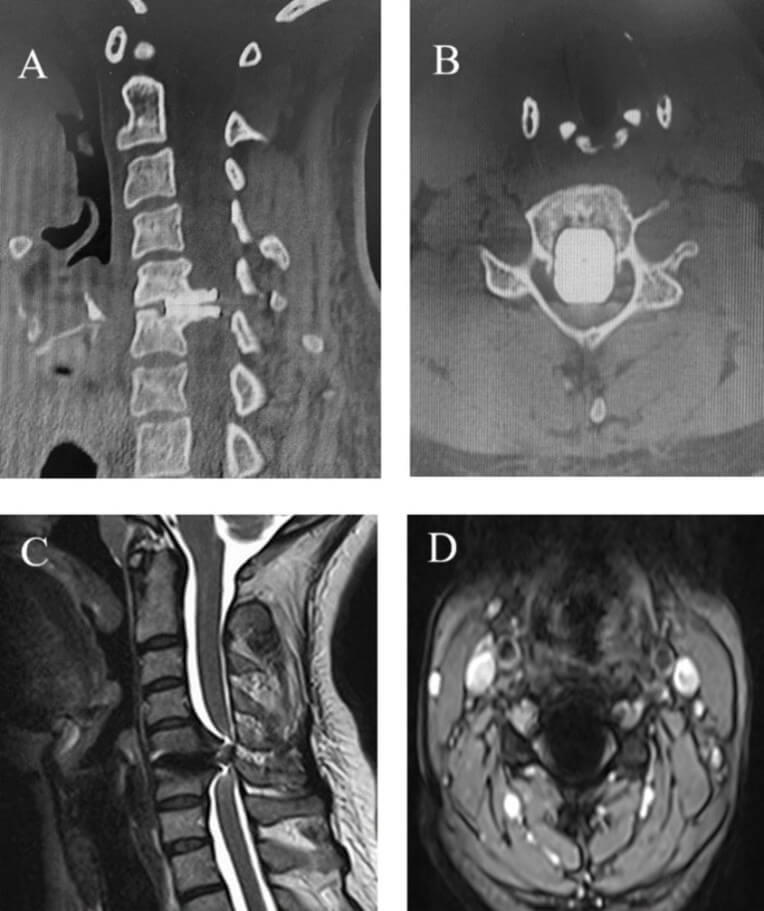

Surgical intervention has been performed using an anterior approach. The prosthesis was successfully removed, and stabilization was achieved with a cage and plate without difficulty. Intraoperative findings revealed a fracture at the central screw retention point of the prosthesis (Figure 2). The patient demonstrated significant neurological recovery, with improved muscle strength and gait on the first postoperative day. She was discharged on the second postoperative day without complications.

A) Sagittal and B) axial CT images, C) sagittal T2 and D) axial T2 MR images. The migrated cervical prosthesis occupies more than half of the spinal canal and compresses the spinal cord. MR images are suboptimal due to metal artifact.

A) The broken superior part of the prosthesis, B) the broken cervical prosthetic parts, C) The postoperative sagittal CT images of the cervical spine.

3. Discussion

Migration is an uncommon but serious complication of CDA, potentially leading to spinal cord compression and significant neurological deficits. The literature documents a variety of factors contributing to such events, including insufficient osseous integration, trauma, and implant design issues [1-12].

Because we don’t have postoperative radiological images after the initial CDA implantation surgery, it is not possible for us to exactly know when and how that migration occurred. Considering the patient had no complaints at the time of CDA implantation surgery, we believe that the migration had occurred sometime after the surgery. The migration should occur slowly and gradually by time, because the patient could be stayed symptomless for a long time despite marked cord compression, suggesting compensation mechanisms took in place. Such a migration is a clear sign of failure of osteointegration of the implant to the endplates. Because a CDA is expected to allow physiological flexion and extension movements, it is plausible to say those movements might contribute gradual migration of the implant into the canal. We detected a fracture at the central screw retention point of the prosthesis, and that could also contribute to the migration. We speculate that risk of such a migration would be less in an implant, which is a cage, who restrict the segmental motion and aims to fuse segment. That point illustrates importance of design properties, durability and its capacity to retain its location of a disc prothesis, because it is expected retain those properties for the lifetime of a patient. In this regard, suboptimal placement technique of a disc prosthesis could also contribute to migration, because it may hinder its function and durability. Thus, again comparing with a cage, surgical technique of a disc prosthesis seems much more critical and much less forgiving.

Surgical removal of the migrated prosthesis and stabilization with alternative constructs, such as cages and plates, is the mainstay treatment. Early intervention often leads to favorable neurological outcomes. Previous reports highlight various migration patterns, including anterior, posterior, and lateral displacements. Factors such as implant design, surgical technique, and patient activity levels postoperatively are critical in determining outcomes [1, 5, 7, 10, 11, 12]. The fractured prosthesis in this case underscores the need for robust designs capable of enduring biomechanical stresses. Advances in materials and fixation mechanisms could mitigate such risks [2, 6, 12].

4. Conclusion

This case underlines the significance of early recognizing and managing rare complications of CDA. The successful surgical intervention highlights the importance of accurate diagnosis, timely surgical correction, and appropriate postoperative care. Further research is warranted to enhance prosthesis design and optimize patient selection criteria to minimize such complications.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable. This is a case report. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Consent

Written informed consent for the publication of this case report and accompanying images was obtained from the patient. A copy of the consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief upon request.

Author Contributions

Isa Isaoglu: Study conception, data collection, manuscript writing. Cumhur Kilinfer: Data interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript.

Guarantor

Isa Isaoglu.

REFERENCES

[1] Scott C Wagner, Daniel G Kang, Melvin

D Helgeson “Traumatic migration of the Bryan cervical disc arthroplasty.” Global

Spine J, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. e15-e20, 2016. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[2] Mantu Jain, Sunil Kumar Doki, Manisha

Gaikwad, et al. “Acute migration following dissociation of components of

cervical disc arthroplasty.” Neurol India, vol. 69, no. 4, pp.

1037-1039, 2021. View at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[3] Yann Pelletier, Olivier Gille,

Jean-Marc Vital “An anterior dislocation after Mobi-C cervical disc

arthroplasty.” Asian J Neurosurg, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 719-721, 2020.

View at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[4] Ji-Liang Zhai, Xiao Chang, Jian-Hua

Hu, et al. “A case of implant migration following bi-level cervical disc

arthroplasty.” Chinese Med J, vol. 130, no. 4, pp. 497-499, 2017. View

at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[5] Tianyi Niu, Haydn Hoffman, Daniel C

Lu “Cervical artificial disc extrusion after a paragliding accident.” Surg

Neurol Int, vol. 8, pp. 138, 2017. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[6] Miao Fang, Yong Zeng, Yueming Song

“Migration of cervical spine screws to the sacral canal: A case report.” BMC

Neurology, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 382, 2024. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[7] Thomas P Loumeau, Bruce V Darden,

Thomas J Kesman, et al. “A RCT comparing 7-year clinical outcomes of one level

symptomatic cervical disc disease following ProDisc-C total disc arthroplasty

versus ACDF.” Eur Spine J, vol. 25, no. 7, pp. 2263-2270, 2016. View at:

Publisher Site | PubMed

[8] Alberto Di Martino, Rocco Papalia,

Erika Albo, et al. “Cervical spine alignment in disc arthroplasty: should we

change our perspective?” Eur Spine J, vol. 24, pp. 810-825, 2015. View

at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[9] Shuai Xu, Yan Liang, Zhenqi Zhu, et

al. “Adjacent segment degeneration or disease after cervical total disc

replacement: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.” J Orthop Surg

Res, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 244, 2018. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[10] Zhenxiang Zhang, Wei Zhu, Lixian Zhu,

et al. “Midterm outcomes of total cervical total disc replacement with Bryan

prosthesis.” Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol, vol. 24, pp. S275-S281, 2014.

View at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[11] Maheen Q Khan, Michael D Prim,

Georgios Alexopoulos, et al. “Cervical disc arthroplasty migration following

mechanical intubation: A case presentation and review of the literature.” World

Neurosurg, vol. 144, pp. 244-249,2020. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[12] Francis M Hacker, Rebecca M Babcock, Robert J Hacker “Very late complications of cervical arthroplasty: Results of 2 controlled randomized prospective studies from a single investigator site.” Spine (Phila Pa 1976), vol. 38, no. 26, pp. 2223-2226, 2013. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed