Received: Mon 30, Jun 2025

Accepted: Thu 17, Jul 2025

Abstract

Outcomes of paraesophageal hernia (PEH) onlay repair with bioabsorbable mesh and body mass index (BMI) as risk factor for poor outcomes and recurrence have been previously published. This has not been evaluated in an Australian cohort. We performed a retrospective observational cohort study on patients who underwent laparoscopic PEH onlay repair with Gore Bio-A® mesh between 01/01/2017 and 01/09/2023. Electronic health records from public and private hospitals based in New South Wales were accessed. Patients were grouped according to preoperative BMI (A: BMI <25; B: BMI = 25-29.9; C: BMI = 30-34.9; D: BMI ≥ 35). Symptomatic outcomes, endoscopic recurrence and surgical reintervention rates were evaluated. Chi square tests were used to compare categorical variables. Of 459 patients 71.5% were women. Mean age was 66.9±13.8 years. Mean BMI was 30.6±5.0kg/m2. All cases were completed laparoscopic, with primary PEH repair more common (n = 437; 95.2%) than revisional (n = 22; 4.8%) cases. The number of patients in BMI groups were as follows; A: 45 (9.8%); B: 195 (42.5%); C: 146 (31.8%); D: 73 (15.9%). 97.8% patients had mean follow-up of 15.1±2.4 months. At last follow-up, 89.7%, 4.5% and 5.8% had resolution, unchanged or recurrent symptoms respectively. Overall postoperative complication rate was (n= 30/449; 6.6%), with (n = 23/280; 8.2%) endoscopic recurrence and (n = 6/449; 1.3%) surgical reintervention rate at last follow-up. No significant difference between BMI groups were observed for symptom resolution (p = 0.64), endoscopic recurrence (p = 0.35), complications (p = 0.11) or need for surgical intervention (p = 0.22). Laparoscopic primary and revisional PEH repair with Gore Bio-A® mesh is safe and effective in a cohort of Australian patients with excellent short-term outcomes and acceptable symptomatic recurrence rate irrespective of BMI.

Keywords

Paraesophageal hernia, mesh, gastroesophgeal reflux, body mass index

1. Introduction

Paraesophageal hernia (PEH) remains an increasingly common diagnosis in an aging western population. With liberal use of proton pump inhibitors many patients manage their suspected gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) initially without any formal investigations. With higher frequency of medical imaging, PEH are more frequently diagnosed which has led to more referrals to a specialist. The treatment of PEH and their associated symptoms can be challenging and may require collaboration among subspecialists. It is important for surgeons to highlight the indication for surgery, have a well-informed discussion and explain to the patients the symptoms that are likely to be relieved from surgery and those symptoms that may persist or occasionally worsen following surgery.

Mesh reinforcement in PEH repair has always been controversial, and some surgeons avoid mesh cruroplasty due to lack of convincing scientific evidence, the risk of severe complications, and the technical challenges of revisional surgery [1]. Severe complications of significant dysphagia, mesh erosion, and fibrosis which occasionally required resectional procedures have led to surgeons taking a more caution approach when considering use of permanent mesh in the hiatal space [2].

Consequently, bioabsorbable mesh gained popularity as it held the promise of avoiding these complications inherent to permanent meshes while providing reinforcement to crural closure. Lima et al. [3] in 2023 published their qualitative systematic review which analyzed 18 studies with 1846 patients and demonstrated that use of bioabsorbable mesh is safe and effective for hiatal hernia repair with low complications rates and high symptom resolution. The reported recurrence rates were variable between 0.9 to 25% due to significant heterogeneity in defining and evaluating recurrences [3]. Obesity has been previously demonstrated to be considered a risk factor for recurrence of hiatus hernia following surgery [4].

There has been no study published to date based on an Australian population regarding outcomes of PEH repair using bioabsorbable mesh. We aim to publish the first study in Australia demonstrating PEH onlay repair outcomes using bioabsorbable Gore Bio-A® mesh and the evaluate the association with body mass index (BMI).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The study adheres to the methodology of strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [5]. Ethical approval was sought from the Nepean Blue Mountains Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (2024/ETH00753). A retrospective observational multicenter cohort study was performed.

2.2. Setting

Patients who underwent laparoscopic PEH repair with or without fundoplication and had onlay Gore Bio-A® mesh crural augmentation at participating public and private hospitals in New South Wales, Australia between the period of 01 January 2016 till 01 January 2023 were included in the study. A total of five surgeons contributed participants to the study operating across three public hospital and five private hospitals.

2.3. Data Sources

Electronic health records from respective hospitals and private consulting rooms were accessed to record demographic, operative and follow-up data. The operative report and outpatient letters were accessed to gain missing information and reviewed until 31st December 2024 to identify symptom progress, repeat investigations and procedures. New South Wales public system is unique such that all public patients have their preoperative work up and follow up with the surgeon in the private consulting rooms and hence most patients had consistent follow up with the operating surgeon.

2.4. End Points

Patients were categorized into one of four groups according to their preoperative BMI. The groups were delineated as follows: Group A: BMI < 25 kg/m2; Group B: BMI = 25-29.9 kg/m2; Group C: BMI = 30-34.9 kg/m2; and Group D: BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2. Primary end points were symptomatic outcomes, ongoing proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use, endoscopic recurrence, complications and surgical reintervention rates. Secondary end point was to assess if the body mass index influenced the primary end points. Symptomatic outcomes were categorized into three groups; resolved defined as complete resolution of preoperative symptoms, unchanged defined as ongoing presence of any of the preoperative symptoms, recurred defined as initial improvement and subsequent recurrence of symptoms. Endoscopic recurrence was defined as any gastric tissue above the diaphragmatic hiatus [6] on postoperative gastroscopy. Complications were graded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification. Surgical reintervention is defined as reoperation for symptomatic recurrence of PEH. Routine follow up was common at one, three, six months and routine gastroscopy at twelve months or earlier if any issues.

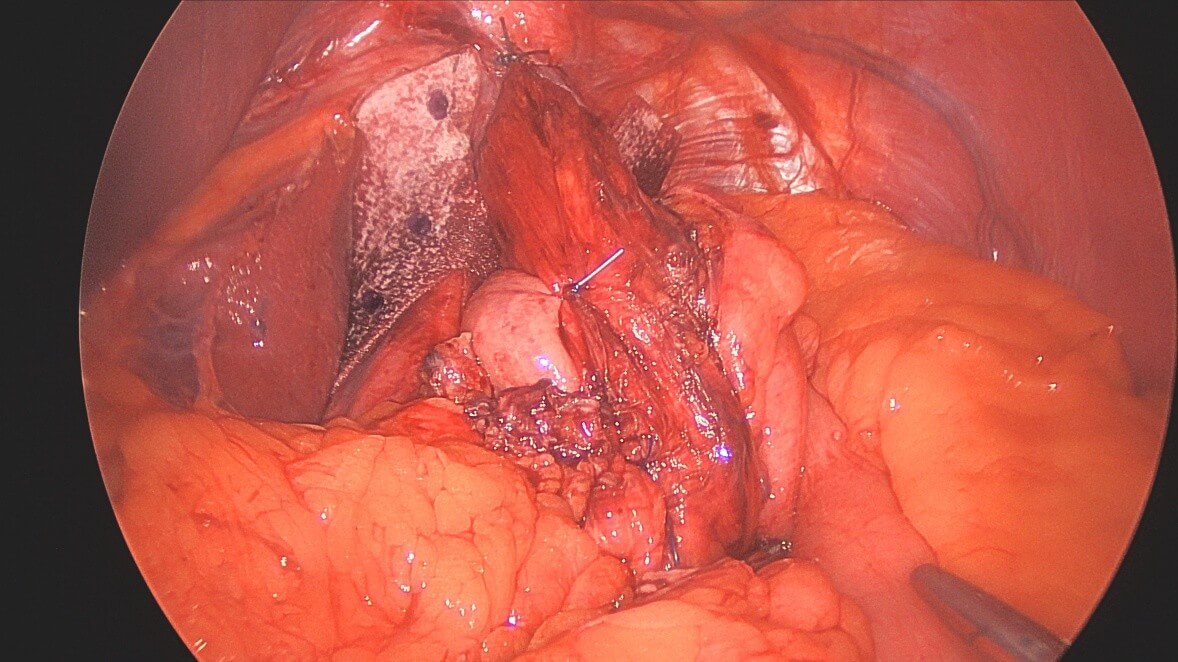

2.5. Surgical Technique

A four-port technique with Nathanson liver retractor were used for the laparoscopic approach. The first step of the operation consisted of reduction of the herniated sac including the stomach or any other organs. 360-degree mediastinal dissection was performed to allow mobilisation of at least five centimeters of tension-free intra-abdominal esophagus whilst preserving both vagal nerves. Primary posterior cruroplasty was routinely performed using interrupted, non-absorbable sutures. Additional anterior cruroplasty using non-absorbable suture was performed at the discretion of the surgeon. The indication to use a mesh was based on the presence of a large hiatal hernia, the subjective surgeon’s feeling of weak crura, and the frailty of crura tissue noticed upon knotting the sutures. A pre-shaped bioabsorbable mesh with a ‘‘U’’ configuration (Gore Bio-A® tissue reinforcement, Flagstaff, AZ) was implanted over the hiatus surface as onlay fashion posterior to the esophagus (Figure 1). Method of fixation of the mesh was up to the surgeon discretion and could involve non-absorbable suture, absorbable tacks, glue or a combination. Fundoplication was routinely performed using non-absorbable suture, and the type was at the discretion of the surgeon. A standardized postoperative protocol to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting was routinely used.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Continuous data were presented as mean and standard deviation. Categorical variables were shown as numbers and percentages. The analysis of variance was used to compare continuous variables, and Chi square tests were used to compare categorical variables. Statistical significance was considered when p value was equal or less than 0.05. Confidence interval was set at 95% confidence level. All analyzes were carried out using GraphPad Prism 10.4.1 software version.

3. Results

We identified a total of 515 patients who underwent laparoscopic PEH repair and fundoplication with or without mesh between 01/01/2017 and 01/09/2023 at these participating hospitals. Out of which 459 patients underwent laparoscopic PEH repair and fundoplication with mesh, all using Gore Bio-A® mesh and these patients were included in the study. Demographic data (Table 1) demonstrated a mean age of 66.9 years and majority of patients were female (71.5%). 94.9% were elective cases and 95.2% were primary procedures. Mean BMI was 30.6±5.0kg/m2. Most predominant preoperative symptom in those patients undergoing surgery was regurgitation (67.7%). All cases were completed laparoscopically with 53.1% cases having <50% gastrothorax and 44.9% patients having ≥ 50% gastrothorax (Table 2).

Table.

1. Clinical

presentation of patients undergoing paraesophageal hernia repair.

|

Variable |

Total (N=459) |

|

Mean

age at time of surgery, years (SD†) |

66.9 (13.8) |

|

Gender,

n (%) -

Male -

Female |

131

(28.5) 328

(71.5) |

|

Timing

of surgery, n (%) -

Elective -

Emergency |

436

(94.9) 23

(5.1) |

|

Category

of surgery, n (%) -

Primary -

Revisional |

437

(95.2) 22

(4.8) |

|

Groups

based on preoperative BMI, n (%) -

A (BMI <25) -

B (BMI=25–29.9) -

C (BMI=30–34.9) -

D (BMI≥ 35) |

45 (9.8) 195

(42.4) 146 (31.8) 73

(16.0) |

|

Preoperative

predominate symptom, n (%) -

Heartburn -

Regurgitation -

Epigastric or chest pain -

Shortness of breath -

Dysphagia -

Combination of two or more above symptoms |

15

(3.3) 311

(67.7) 28

(6.2) 14

(3.0) 61

(13.3) 30

(6.5) |

†SD standard deviation.

Table.

2. Perioperative

characteristics of patients undergoing paraesophageal hernia repair.

|

Variable |

Total (N=459) |

|

Mode of

surgery, n (%) -

Laparoscopic -

Conversion to open |

459

(100) 0 (0) |

|

%

gastrothorax, n (%) -

< 50% -

≥ 50% -

Unavailable |

244

(53.2) 206

(44.8) 9 (2.0) |

|

Type of

fundoplication, n (%) -

Anterior 180 degree -

Posterior 270 degree -

Nissen 360 degree -

Unavailable |

260

(56.6) 182

(39.7) 6 (1.3) 11

(2.4) |

|

Method

of Bio-A® mesh fixation, n (%) -

Non absorbable suture -

Glue -

AbsorbaTack -

Suture and Glu -

Suture and AbsorbaTack |

223

(48.6) 130

(28.3) 100

(21.9) 3 (0.6) 3 (0.6) |

The number of patients in BMI groups were as follows; A: 45 (9.8%); B: 195 (42.5%); C:146 (31.8%); D: 73 (15.9%) (Table 3). There were ten patients (2.2%) lost to follow up with 97.8% patients had at least one follow up and mean follow-up time of 15.1 ± 2.4 months. At last follow-up, 89.7%, 4.5% and 5.8% had resolution, unchanged or recurrent symptoms, respectively. Overall postoperative complication rate was (n = 30/449; 6.6%), with (n = 23/280; 8.2%) endoscopic recurrence and (n = 6/449; 1.3%) surgical reintervention rate at last follow-up. There were no mesh related complications. No significant difference between BMI groups were observed for ongoing use of PPI (0.43), symptom resolution (p = 0.64), endoscopic recurrence (p = 0.35), complications (p = 0.11) or need for surgical intervention (p = 0.22) (Table 3).

Table.

3. Postoperative

outcomes based on body mass index groups.

|

Variable |

Total (N=459) |

Body mass index |

P value |

|||

|

A (N=45) |

B (N=195) |

C (N=146) |

D (N=73) |

|||

|

Mean

duration of clinical FU†, months (SD‡) |

15.1 (12.4) |

12.6

(14.6) |

15.7

(12.6) |

14.3

(11.4) |

15.8

(12.6) |

|

|

Lost to

FU, n (%) |

10 (2.2) |

1 (2.2) |

5 (2.6) |

2 (1.7) |

2 (2.7) |

0.539 |

|

Ongoing

use of PPI§, n (%) -

Yes -

No -

Unavailable |

89

(20.0) 355

(80.0) 5 |

10

(23.2) 33

(76.8) 1 |

36

(19.3) 151

(80.7) 3 |

33

(23.1) 110

(76.9) 1 |

10

(14.1) 61

(85.9) 0 |

0.433 |

|

Symptoms

at last FU, n (%) -

Resolved -

Unchanged -

Recurred |

403

(89.7) 20

(4.5) 26

(5.8) |

40

(90.0) 2 (4.5) 2 (4.5) |

171

(90.0) 8 (4.2) 11

(5.8) |

132

(91.7) 4 (2.8) 8 (5.5) |

60

(84.5) 6 (8.5) 5 (7.0) |

0.639 |

|

Endoscopic

recurrence at last FU, n (%) -

Yes -

No -

Unavailable |

23

(8.2) 261 (91.8) 165 |

0 (0) 22

(100) 22 |

9 (7.3) 114

(92.7) 67 |

7 (7.7) 84

(92.3) 53 |

7

(14.6) 41

(85.4) 23 |

0.352 |

|

Complications

Clavien–Dindo grade, n (%) Total -

Grade I -

Grade II -

Grade III -

Grade IV -

Grade V |

30

(6.7) 9 (2.0) 8 (1.8) 12

(2.7) 1 (0.2) 0 (0.0) |

3 (6.8) 2 (4.5) 0 (0.0) 1 (2.2) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

12

(6.3) 6 (3.2) 2 (1.0) 3 (1.6) 1 (0.5) 0 (0.0) |

14

(9.7) 1 (0.6) 6 (4.2) 7 (4.9) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

1 (1,4) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 1 (1.4) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

0.107 |

|

Need

for surgical reintervention, n (%) |

6 (1.3) |

1 (2.2) |

2 (1.0) |

1 (0.6) |

2 (2.7) |

0.221 |

†FU follow up; ‡SD standard deviation §PPI proton pump inhibitor.

4. Discussion

Laparoscopic PEH repair with fundoplication remains the treatment of choice for patients with symptomatic PEH and has demonstrated excellent outcomes in selected patients. Surgeons remain divided with regards to their preferences for mesh augmented cruroplasty versus primary repair. Surgeons would argue against mesh, based on the scientific evidence available and in most cases personal experiences with patients having severe mesh related complications such as dysphagia, erosion and certain revisional cases even requiring resection. We demonstrated Gore Bio-A® mesh augmented cruroplasty is safe in primary or revisional setting with excellent short-term outcomes and acceptable symptomatic recurrence rate irrespective of BMI.

There have been a few meta-analyzes recently published assessing hiatus hernia repair outcomes with mesh versus primary suture repair and also evaluated the outcomes based on type of mesh. Rajkomar et al. [7] which evaluated five randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and thirteen observational studies with 1670 patients (824 with no mesh, 846 with mesh) showed significant reduction in the total recurrence rate with mesh (OR 0.44, p = 0.007). However, subgroup analysis showed mesh use did not cause significant reduction in larger recurrences > 2 cm (OR 0.94, p = 0.83) or in reoperation rates (OR 0.64, p = 0.09). Cases of mesh erosion with eventual foregut resection were noted and were associated with synthetic meshes only. Temperley et al. [8] in 2023 evaluated eight RCTs with 766 patients and demonstrated non-absorbable mesh (NAM) had significantly lower early recurrence rates (OR: 0.225, p < 0.05) compared with suture repair alone; however, no differences in late recurrences were evident. For absorbable mesh (AM), no difference in early or late recurrence rates were evident compared with the suture only group. In this study they had limited data comparing patients NAM versus AM, hence they were unable to conclude which composition was significant. Interestingly none of the eight RCTs used Gore Bio-A® mesh. The commonly used NAM were TiMesh, polypropylene, ProGrip, polytetrafluoroethylene and one study used AM which was Surgisis.

Bio-A® mesh is a copolymer of polyglycolic acid and trimethylene carbonate (PGA: TMC) in a three-dimensional matrix and produced by WL Gore. Bioabsorbable mesh are designed to maintain their structure long enough for tissue ingrowth, but completely degrade in approximately 6 to 7 months in the case of Gore Bio-A® mesh [9] and up to 2 years for Phasix mesh [poly-4-hydroxybutyrate (P4HB)], which is produced by Bard [10]. This theoretically prevents mesh related long-term complications such as erosion requiring resection. Clapp et al. [11] analyzed twelve bioabsorbable mesh studies (eleven Gore Bio-A® mesh and one Phasix mesh) had a significantly lower recurrence rate compared to nine non-mesh studies (8% vs. 18%, p < 0.0001). It is important to note that none of the Gore Bio-A® mesh studies were RCTs or based in Australia and the selected non-mesh studies were randomly selected without any specific inclusion criteria. Petric et al. [12] performed a metanalysis of the seven RCTs comparing mesh versus primary suture repair and showed no significant differences for short-term hernia recurrence (defined as 6-12 months, 10.1% mesh vs 15.5% sutured, p = 0.22), long-term hernia recurrence (defined as 3-5 years, 30.7% mesh vs 31.3% sutured, p = 0.69), functional outcomes and patient satisfaction. Even though our study did not have a comparison group based on the limiting data and short term follow up, our series had and endoscopic PEH recurrence rate of 8.2% with a mean follow up of 15.1 months. One of the significant issues highlighted include the heterogeneity in definition of recurrence of hiatus hernia between studies [6, 11]. This highlights the importance of future studies to have well-defined surgical and endoscopic measurable outcomes which would allow comparison across studies.

The correlation between radiological or endoscopic recurrence has been shown to be poor with symptoms and need for revisional surgery. Studies have shown objective recurrent hiatal hernia to be symptomatic in only 11% of patients [13]. The need for surgical reintervention for symptomatic PEH recurrence was low at 1.3% in our series. Both latest reviews evaluating laparoscopic PEH repair with Gore Bio-A® mesh cruroplasty showed significant improvement in symptom scores as well as a sustained improvement in quality of life over time and satisfaction [3, 11]. This is consistent with our study which demonstrated 89.7% of patients had symptom resolution at the last follow up and 80% of patients were able to come off the PPI. In addition, none of the studies published on Gore Bio-A® mesh outcomes have reported any cases of mesh erosion or explant [3, 11]. Our study resonated the same with no mesh related complications. Our total complication rate was 6.6% with majority Grade III complications. This was due to 10 patients (2.2%) requiring gastroscopy and serial dilatations for dysphagia during the follow up period, none requiring revisional surgery. Armijo et al. [14] had similar complications with 7.2% (6/83 patients) requiring gastroscopy and serial dilatations for dysphagia none requiring revision surgery. In our study we were unable to ascertain if the mesh contributed directly to it or if it was simply due to a mechanical constraint from a tight cruroplasty and/or wrap. If dysphagia was mesh-related due to fibrosis, it is usually persistent and troublesome with some relief from dilation, but usually requires reoperation and explant. This was supported by Zhang et al. [15] meta-analysis which compared postoperative dysphagia at one-year follow-up in all studies with or without mesh augmentation and demonstrated that the prevalence of postoperative dysphagia was not significantly increased following mesh-augmentation.

Morbid obesity is a known risk factor for PEH recurrence and poor postoperative outcomes [4]. Olson et al. [16] published the largest series to date evaluating long-term outcomes in patients who underwent laparoscopic PEH repair with Gore Bio-A® mesh cruroplasty and the only study that investigated if BMI played a role in increasing reintervention rate in these patients. The study evaluated four groups of patients based on their BMI (< 25; 25-29.9; 30-34.9; ≥ 35). They demonstrated that during the mean follow-up time of 54.0 ± 13.1 months, there was no significant difference across all four groups in symptomatic recurrence, the interval between primary PEH repair and reoperation, and the probability of surgical reintervention for a recurrence. 89.4% patients reported good to excellent satisfaction postoperatively, with no significant differences among the groups. Our study investigated the same question in Australian setting and resonated the same result. We demonstrated that there was no difference between the BMI groups in terms of immediate complications, endoscopic recurrence, symptom resolution, ongoing PPI use and need for surgical re-intervention.

A limitation of the existing literature irrespective of PEH repair was performed with or without mesh is the intraoperative non-measurable factors that could relate to recurrence is not well documented. These include retention of the hernia sac, weak muscle fibers of the crura, inadequate mobilisation of the esophagus and tension on the crural repair. Regardless of the use of any type of mesh it is important that meticulous mediastinal dissection is performed, hernia sac is completely reduced with its content, complete mobilisation of the esophagus is performed to achieve at least 5 cm of intrabdominal esophageal length to reduce risk of recurrence. Future studies should also focus on these factors when evaluating outcomes of hiatal hernia surgery.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest case series published in English language discussing the outcomes of Gore Bio-A® mesh use in the reinforcement of PEH repair. It is the first series published in Australia on patient outcomes with the use of Gore Bio-A® mesh for PEH repair. We believe having multicenter involvement in this study adds to the strength of the findings, support the use of Gore Bio-A® mesh for PEH repair and encourages other surgeons. There are several limitations of our study. This was a retrospective observation study and the comparative efficacy of Gore Bio-A® mesh reinforcement versus without cannot be ascertained, as there was no control arm. Even though all surgeons followed the general steps of the above-described surgical technique given the multicenter nature of this study there could be slight variations in the repair, mesh shaping and fixation methods which could affect the outcomes. A detailed questionnaire and satisfaction survey that offered a more comprehensive post-operative symptom description was not performed for the purpose of the study, apart from what was reported to the patient during their follow up. There was significant proportion of patients who did not have data available (37%) on endoscopic recurrence as either this was not routinely performed, or the data was missing on the last follow up. There could have been patients who went on to have surgical reintervention with a different surgeon not captured in this follow up. Prospectively maintained data base with regular reminders to patients to complete their follow up questionnaires would allow surgeons to monitor their progress to provide best outcome for their patients.

5. Conclusion

The study confirms that laparoscopic primary and revisional PEH onlay repair with Gore Bio-A® mesh is safe and effective in a cohort of Australian patients with excellent short-term outcomes and acceptable symptomatic recurrence rate irrespective of BMI. Randomized multicenter studies with patient centered long term outcomes would be beneficial to validate the findings.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgment(s) and Author Contributions

Authors would like to acknowledge Dr Ken Loi for his contribution to this series. Specific author contributions: Conceptualisation: Janindu Goonawardena, Jasmine Mui, Linda Tang, Junaid Syed, Mark Richardson, Han Liem, Qiuye Cheng, Kamala Das, Michael Devadas; Methodology: Janindu Goonawardena, Jasmine Mui, Linda Tang, Junaid Syed, Qiuye Cheng, Michael Devadas; Formal analysis: Janindu Goonawardena, Jasmine Mui. Supervision: Mark Richardson, Han Liem, Qiuye Cheng, Kamala Das, Michael Devadas; Manuscript writing: Janindu Goonawardena, Jasmine Mui; Editing and reviewing: Janindu Goonawardena, Jasmine Mui, Qiuye Cheng, Mark Richardson, Han Liem, Qiuye Cheng, Kamala Das, Michael Devadas.

REFERENCES

[1] Yashodhan

S Khajanchee, Robert O'Rourke, Maria A Cassera, et al. “Laparoscopic

reintervention for failed antireflux surgery: subjective and objective outcomes

in 176 consecutive patients.” Arch Surg, vol. 142, no. 8, pp. 785-901,

2007. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[2] Kalyana

Nandipati, Maria Bye, Se Ryung Yamamoto, et al. “Reoperative intervention in

patients with mesh at the hiatus is associated with high incidence of

esophageal resection--a single-center experience.” J Gastrointest Surg,

vol. 17, no. 12, pp. 2039-2044, 2013. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[3] Diego

L Lima, Sergio Mazzola Poli de Figueiredo, Xavier Pereira, et al. “Hiatal

hernia repair with biosynthetic mesh reinforcement: a qualitative systematic

review.” Surg Endosc, vol. 37, no. 10, pp. 7425-7436, 2023. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[4] Brett

C. Parker, Reid Fletcher, Alsadiq Bin Eisa, et al. “The Impact of Body Mass

Index on Recurrence Rates Following Laparoscopic Paraesophageal Hernia Repair.”

Foregut, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 172-182, 2022. View at: Publisher Site

[5] Erik

von Elm, Douglas G Altman, Matthias Egger, et al. “The Strengthening the

Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement:

guidelines for reporting observational studies.” Ann Intern Med, vol.

147, no. 8, pp. 573-577, 2007. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[6] James

M Tatum, John C Lipham “Recurrent Hiatal Hernia: Evolving Definitions and

Clinical Implications.” Clin Surg, vol. 3, pp. 1884, 2018.

[7] K

Rajkomar, C S Wong, L Gall, et al. “Laparoscopic large hiatus hernia repair

with mesh reinforcement versus suture cruroplasty alone: a systematic review

and meta-analysis.” Hernia, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 849-860, 2023. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[8] Hugo

C Temperley, Matthew G Davey, Niall J O'Sullivan, et al. “What works best in

hiatus hernia repair, sutures alone, absorbable mesh or non-absorbable mesh? A

systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials.” Dis

Esophagus, vol. 36, no. 7, pp. doac101, 2023. View at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[9] James

M Massullo, Tejinder P Singh, Ward J Dunnican, et al. “Preliminary study of

hiatal hernia repair using polyglycolic acid: trimethylene carbonate mesh.” JSLS,

vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 55-59, 2012. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[10]

David P Martin, Amit Badhwar, Devang

V Shah, et al. “Characterization of poly-4-hydroxybutyrate mesh for hernia

repair applications.” J Surg Res, vol. 184, no. 2, pp. 766-773, 2013.

View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[11]

Benjamin Clapp, Ali M Kara, Paul J

Nguyen-Lee, et al. “Does bioabsorbable mesh reduce hiatal hernia recurrence

rates? A meta-analysis.” Surg Endosc, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 2295-303,

2023. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[12]

Josipa Petric, Tim Bright, David S

Liu, et al. “Sutured Versus Mesh-augmented Hiatus Hernia Repair: A Systematic

Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.” Ann Surg,

vol. 275, no. 1, pp. e45-e51, 2022. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[13]

Edgar J B Furnée, Werner A Draaisma,

Rogier K Simmermacher, et al. “Long-term symptomatic outcome and radiologic

assessment of laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair.” Am J Surg, vol. 199,

no. 5, pp. 695-701, 2010. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[14]

Priscila R Armijo, Crystal Krause,

Tailong Xu, et al. “Surgical and clinical outcomes comparison of mesh usage in

laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair.” Surg Endosc, vol. 35, no. 6, pp.

2724-2730, 2021. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[15]

Chao Zhang, Diangang Liu, Fei Li, et

al. “Systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic mesh versus suture

repair of hiatus hernia: objective and subjective outcomes.” Surg Endosc,

vol. 31, no. 12, pp. 4913-4922, 2017. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[16] Michael T Olson, Saurabh Singhal, Roshan Panchanathan, et al. “Primary paraesophageal hernia repair with Gore® Bio-A® tissue reinforcement: long-term outcomes and association of BMI and recurrence.” Surg Endosc, vol. 32, no. 11, pp. 4506-4516, 2018. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed