Received: Sat 12, Jul 2025

Accepted: Thu 07, Aug 2025

Abstract

Purpose: This study aimed to comparatively evaluate the performance of large language models (LLMs) and large reasoning models (LRMs) in addressing clinical management challenges associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), a complex domain within radiation oncology.

Methods: Five AI models, three LLMs (GPT-4, GPT-4o, and Gemini 2.0 Flash) and two LRMs [Deepseek-R1 and Grok 3 (Think)], were assessed using a custom-designed set of 50 open-ended questions spanning five key modules of NPC management. Responses were independently scored by two radiation oncologists in a single-blinded manner using a standardized rubric. Statistical analyses were conducted to compare model performance.

Results: The LRMs achieved higher mean scores (range: 16.66-17.44) than the LLMs (range: 14.04-15.54). Overall, Grok 3 (Think) and Deepseek-R1 significantly outperformed ChatGPT-4 and Gemini 2.0 Flash, while GPT-4o demonstrated superior performance compared to ChatGPT-4 (P = 0.047). Module-specific analyses revealed that Grok 3 (Think) and Deepseek-R1 consistently outperformed others, particularly in complex domains such as multidisciplinary treatment and radiotherapy. In multidimensional assessment, Grok 3 (Think) achieved the highest accuracy (84.0%) and relevance (91.6%), whereas Deepseek-R1 excelled in comprehensiveness (83.2%). Nonetheless, all models exhibited notable limitations, including outdated content, hallucinations, and inadequate source attribution.

Conclusion: LRMs demonstrate superior performance compared to LLMs in addressing open-ended clinical questions related to NPC management and hold substantial promise for clinical decision support in radiation oncology. However, rigorous validation and cautious interpretation of AI-generated content remain essential to ensure reliability in clinical practice.

Keywords

Large reasoning models, large language models, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, radiation oncology, clinical decision support, artificial intelligence, comparative evaluation

Highlights

i) The advent of large reasoning models (LRMs) has markedly enhanced the capabilities of generative AI in supporting complex clinical decision-making.

ii) A set of open-ended clinical questions specific to nasopharyngeal carcinoma was developed, offering a focused framework to assess AI performance in radiation oncology.

iii) LRMs, particularly Grok 3 (Think), consistently outperformed conventional large language models (LLMs), demonstrating higher mean scores and improved reliability in clinical decision support.

iv) Despite their promise, LRMs remain susceptible to hallucination errors, emphasizing the critical need for comprehensive validation before clinical implementation.

1. Introduction

Large language models (LLMs) have emerged as a transformative force in generative artificial intelligence (GenAI), enabling machines to understand and generate human-like text with remarkable accuracy and fluency [1, 2]. Among these, ChatGPT4 has become one of the most extensively studied models in the medical domain. Research has demonstrated its potential as a supplementary tool to enhance diagnostic accuracy, streamline data collection, improve patient communication, and support clinical decision-making [3-5]. A landmark randomized controlled trial further validated its utility, showing that ChatGPT4 significantly improved physicians’ clinical decisions in complex scenarios compared to conventional online resources [6]. While ChatGPT4 excels at processing objective data, its performance remains constrained in situations involving subjective interpretation or nuanced clinical judgment [7].

The latest generation of LLMs, including GPT-4o, has introduced even greater capabilities and efficiency, surpassing its predecessor in both reasoning depth and speed [8]. Similarly, Google’s Gemini 2.0 Flash has demonstrated notable advancements over its earlier version, Google Bard [9]. These developments suggest an expanding role for GenAI in clinical workflows. Parallel to these improvements, a new class of AI systems, large reasoning models (LRMs) such as DeepSeek-R1 [10] and Grok 3 (Think) [11], has emerged. Built upon LLM foundations, LRMs incorporate sophisticated reasoning frameworks that allow for stepwise deliberation, mimicking human cognitive processes more closely than traditional LLMs [12, 13]. Despite their promising design, the real-world clinical utility of LRMs, especially in complex, high-stakes medical settings, remains largely untested.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) presents an ideal clinical context for evaluating AI-driven decision support systems in radiation oncology. Effective NPC management demands the integration of diverse clinical tasks: accurate diagnostic staging, individualized radiotherapy planning, complication mitigation, and coordination across multidisciplinary teams [14]. These tasks require not only factual medical knowledge but also probabilistic reasoning, risk-benefit assessments, and interpretation of evolving clinical guidelines, making NPC a robust test case for AI capabilities.

Despite growing interest in LLMs within healthcare, direct comparisons between LLMs and LRMs remain limited, particularly in open-ended clinical scenarios that demand sophisticated reasoning. Addressing this gap, our study systematically evaluates the performance of leading LLMs and LRMs in responding to open-ended clinical management questions specific to NPC. The question set, developed by senior radiation oncology experts, was designed to reflect real-world complexity and decision-making demands, while focusing on a single tumor type to ensure depth of evaluation. Moreover, the use of newly constructed questions minimized the risk of dataset contamination from model training data.

By assessing how well these models handle complex clinical reasoning, formulate evidence-based treatment strategies, and offer contextually relevant recommendations, this study aims to clarify their respective strengths and limitations. Ultimately, the findings may inform strategies for optimizing AI integration into clinical workflows in radiation oncology, supporting more informed, consistent, and high-quality care.

2. Methods

This study compared the performance of three large language models (LLMs), GPT-4, GPT-4o, and Gemini 2.0 Flash, with two large reasoning models (LRMs), Deepseek-R1 and Grok 3 (Think). GPT-4 and GPT-4o, both developed by OpenAI, require a “ChatGPT Plus” subscription for unrestricted access. Gemini 2.0 Flash, developed by Google, is freely available to the public. Deepseek-R1, developed by DeepSeek, is an openly accessible LRM. Grok 3 (Think), part of the Grok model series from xAI, was also publicly available, though full access to advanced features requires an “X Premium+” subscription.

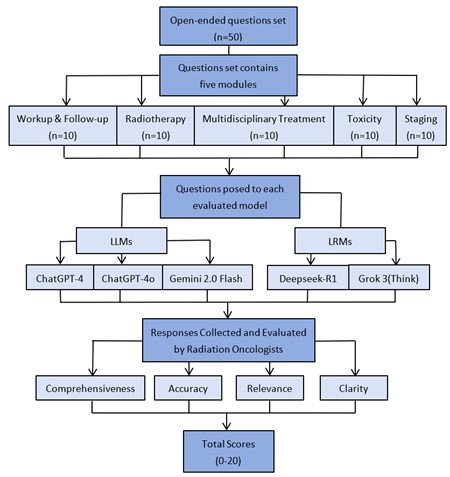

A question set was developed based on the clinical expertise of four board-certified radiation oncologists from academic medical centers, all of whom were attending physicians specializing in head and neck cancers. This set included 50 open-ended questions, evenly distributed across five clinical modules relevant to nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC): i) workup & follow-up, ii) staging, iii) radiotherapy, iv) multidisciplinary treatment, and v) toxicity (Supplementary Table S1). Each question was formulated in scientific language using appropriate clinical terminology. Each of the five AI models was tested using the full question set. Questions were manually submitted to each model in a single, uninterrupted session between February 15, 2025, and March 5, 2025. No additional context, emphasis, or follow-up prompts were provided. All responses were collected and archived (Supplementary Table S2). Responses from each model were independently evaluated by two senior radiation oncologists, each with over 15 years of clinical experience. The evaluators were blinded to the identity of the AI model. Scoring was conducted on a standardized 0-20 scale based on four criteria: i) Comprehensiveness: Degree to which the response addressed all aspects of the question. ii) Accuracy: Alignment of the content with current clinical standards and expert knowledge. iii) Relevance: Appropriateness and topical focus of the response. iv) Clarity: Structural organization and ease of understanding. Scoring criteria were detailed in (Supplementary Table S3). Following independent evaluations, the two assessors resolved scoring discrepancies through discussion and reached a consensus score for each response. The overall study workflow was illustrated in (Figure 1).

Statistical analysis was conducted using Python (version 3.10.12, Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA). Descriptive statistics included measures of central tendency (mean, median) and dispersion (interquartile range [IQR], standard deviation [SD], and coefficient of variation [CV]). Inter-rater reliability was assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Given the limited sample size per module, statistical comparisons focused on total scores across the complete question set. Inter-model performance differences were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. A two-sided P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

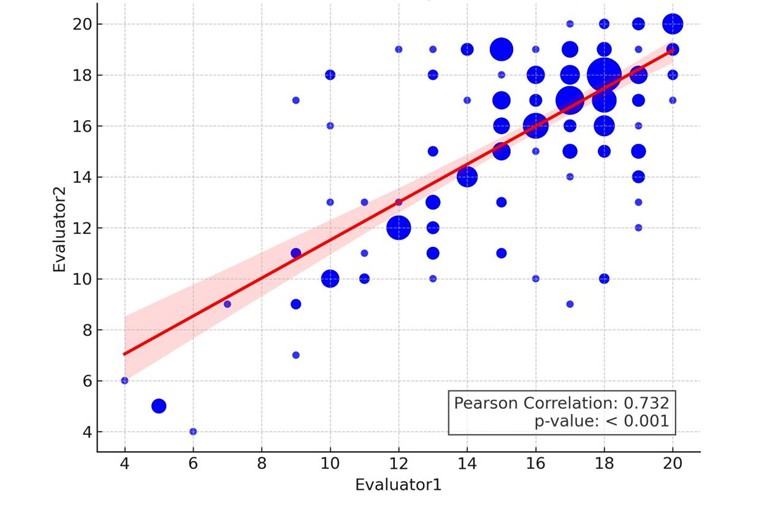

Between February 15, 2025, and March 5, 2025, five models- Grok 3 (Think), Deepseek-R1, ChatGPT-4o, Gemini 2.0 Flash, and ChatGPT-4- were evaluated across clinical tasks. The workflow for this comparative evaluation of LLMs and LRMs is illustrated in (Figure 1). The inter-evaluator reliability of the scoring between the two radiation oncologists across all five models was presented in (Figure 2). A statistically significant correlation was observed, with a Pearson correlation coefficient (r) of 0.732 (P < 0.001), indicating consistent application of the scoring rubric. This finding was further supported by an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.733, confirming good agreement between evaluators. Following independent assessments and reliability validation, consensus-derived scores were established for all model responses.

This scatter plot depicts the correlation between the two evaluators, where point size is determined by frequency-weighted size. A linear regression line (red) is overlaid with the shaded region representing the 95% confidence interval.

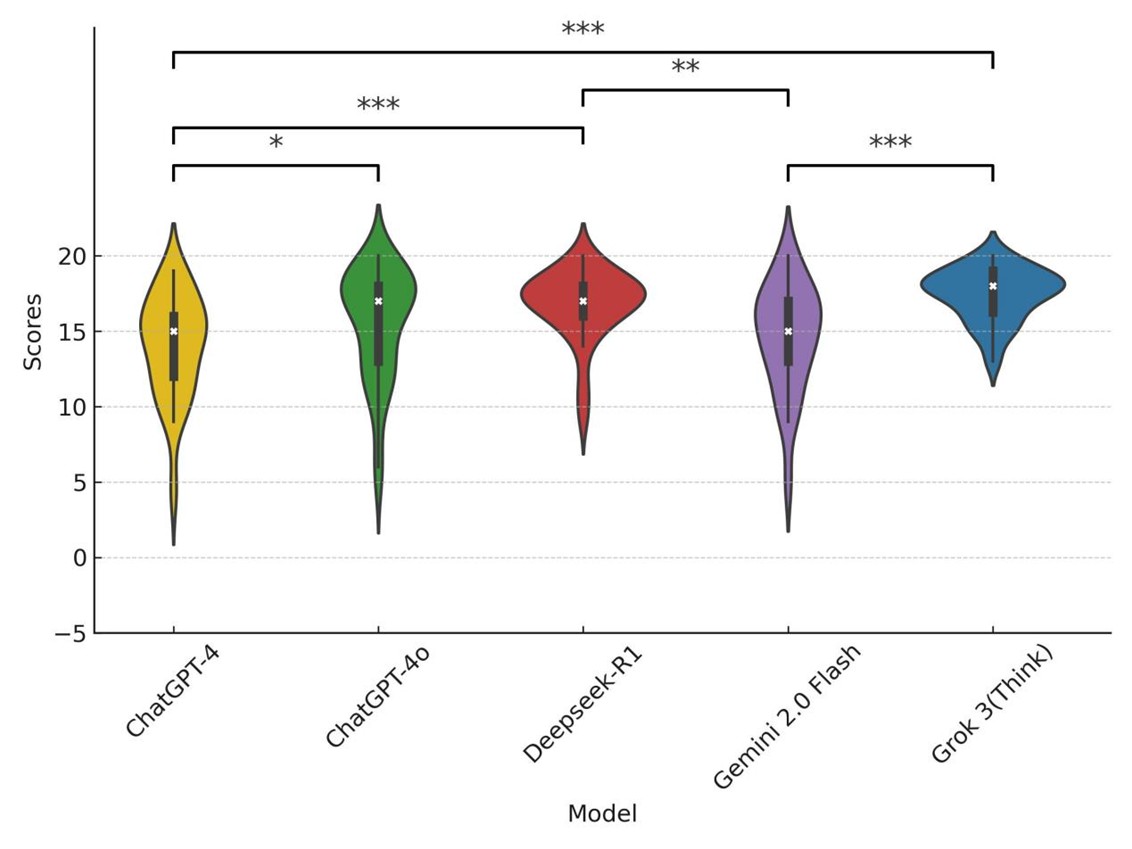

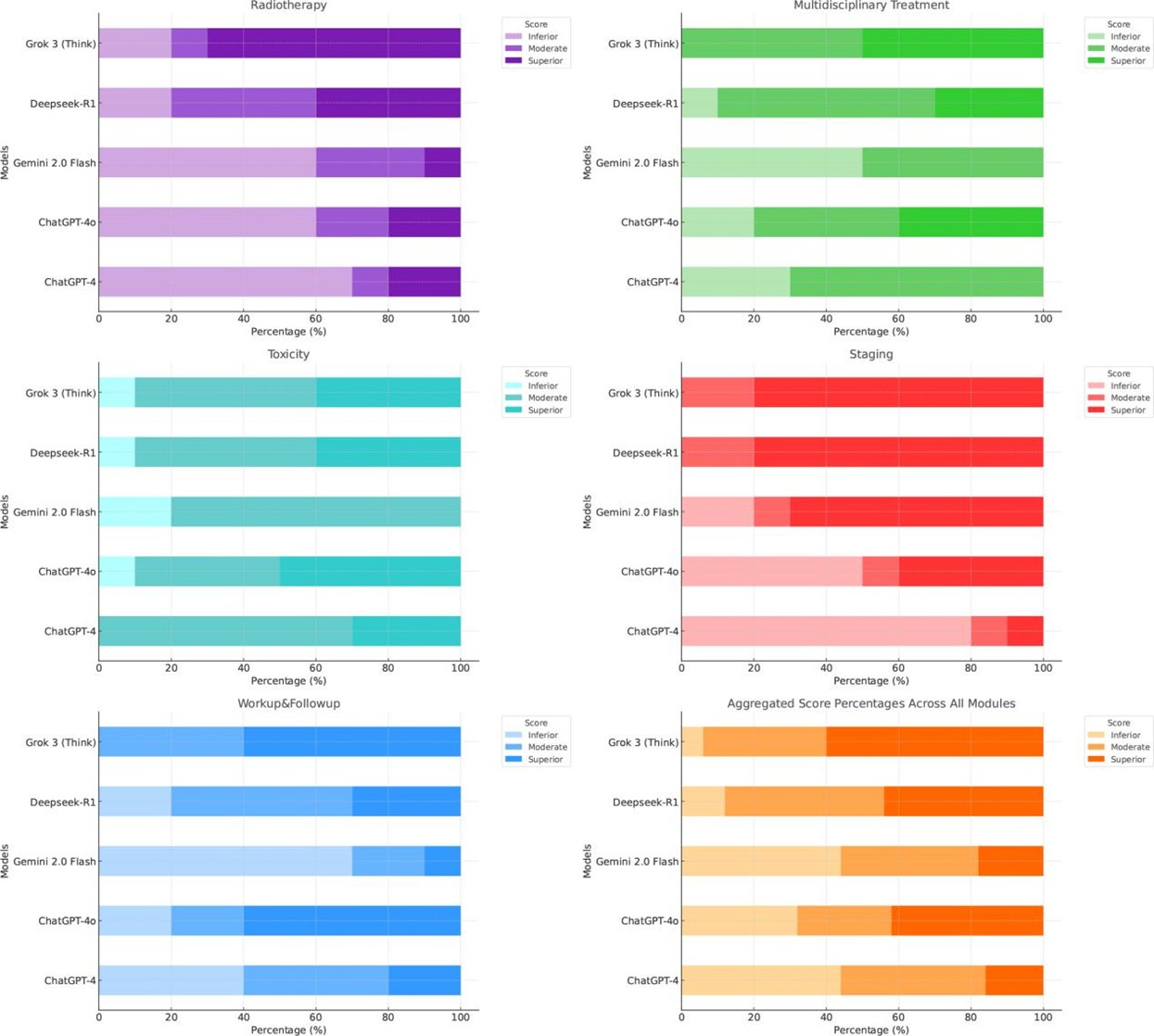

Table 1 presented the descriptive statistics of the finalized scores. The median aggregated score across all models was 17 (interquartile range [IQR]: 14-18). Among the five evaluated models, Grok 3 (Think) achieved the highest mean score (17.44 ± 1.74), followed by Deepseek-R1, ChatGPT-4o, Gemini 2.0 Flash, and ChatGPT-4. The coefficient of variation (CV) revealed that Grok 3 (9.98%) and Deepseek-R1 (13.98%) demonstrated more stable performance. Among the LLMs, ChatGPT-4o recorded the highest mean score (15.54 ± 3.69); however, its higher CV (23.77%) indicated notable performance variability. The Kruskal-Wallis test revealed a statistically significant difference in overall performance among the models (P < 0.001). Post hoc pairwise comparisons using Dunn’s test showed that Grok 3 (Think) significantly outperformed ChatGPT-4 (P < 0.001) and Gemini 2.0 Flash (P < 0.001). Deepseek-R1 similarly outperformed ChatGPT-4 (P < 0.001) and Gemini 2.0 Flash (P < 0.01). A marginally significant difference was observed between ChatGPT-4o and ChatGPT-4 (P = 0.047). No other pairwise comparisons yielded statistically significant differences. Statistically significant comparisons were illustrated in (Figure 3), and the complete pairwise matrix was provided in (Supplementary Table S4). Responses were categorized as inferior (score ≤ 14), moderate (score 15-17), and superior (score ≥ 18), based on the IQR of aggregated scores. A module-specific breakdown of score distributions (Figure 4) revealed notable differences in model performance. The two LRMs, Grok 3 (Think) and Deepseek-R1, consistently delivered a higher proportion of superior responses across all modules. Grok 3 (Think) achieved the highest percentage of superior responses in the workup & follow-up (60%) and radiotherapy (70%) modules, with no inferior responses recorded in workup & follow-up, staging, or multidisciplinary treatment. Deepseek-R1 demonstrated exceptional performance in staging (80% superior) and solid performance in radiotherapy (40% superior), surpassing all LLMs.

Table.

1. Descriptive

statistics for the final scores to the answers provided by the 5 models.

|

|

ChatGPT-4 |

ChatGPT-4o |

Gemini

2.0 Flash |

Deepseek-R1 |

Gork 3 (Think) |

Aggregated

score |

|

Minimum |

4 |

5 |

5 |

9 |

13 |

4 |

|

Median (Interquartile

range) |

15

(12-16) |

17

(13-18) |

15

(13-17) |

17

(16-18) |

18

(16-19) |

17

(14-18) |

|

Maximum |

19 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

|

Mean

(SD) |

14.04

(3.44) |

15.54

(3.69) |

14.62

(3.57) |

16.76

(2.34) |

17.44

(1.74) |

15.68

(3.29) |

|

Coefficient

of Variance |

24.50% |

23.77% |

24.40% |

13.98% |

9.98% |

20.98% |

Statistical significance between models was determined using Dunn’s post hoc with significance levels indicated as follows: *** (p<0.001), ** (p<0.01), and * (p<0.05).

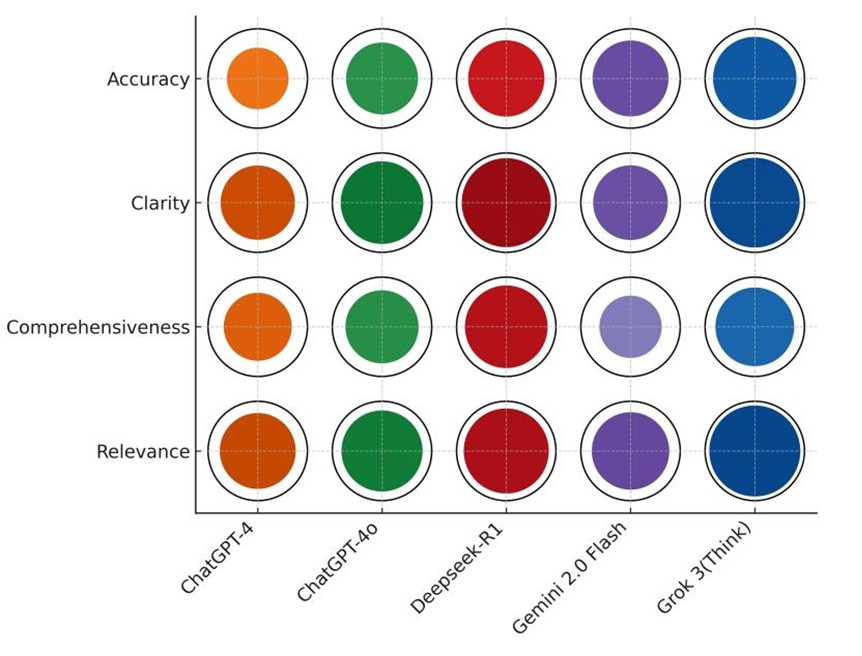

In contrast, ChatGPT4 produced limited high-quality responses, with 0%-10% superior ratings in multidisciplinary treatment and staging. ChatGPT-4o showed moderate improvement, achieving 60% superior responses in workup & follow-up, but exhibited considerable performance volatility, with 40%-50% inferior responses in staging and radiotherapy. Across all models, toxicity management was the most challenging domain, no model exceeded 50% superior ratings, highlighting a shared limitation in handling this topic. A multidimensional evaluation across four criteria, accuracy, relevance, comprehensiveness, and clarity, was presented in (Figure 5). Grok 3 (Think) excelled in accuracy (84.0%) and relevance (91.6%), significantly outperforming ChatGPT-4 (P < 0.001 for accuracy; P = 0.003 for relevance) and Gemini 2.0 Flash (P = 0.002 for accuracy; P = 0.10 for relevance). It also achieved the highest clarity score (90.4%), although inter-model differences in clarity were not statistically significant (P = 0.12).

Deepseek-R1 scored highest in comprehensiveness (83.2%), significantly outperforming ChatGPT-4 (P = 0.02) and Gemini 2.0 Flash (P < 0.001), while also maintaining high clarity (89.6%) and strong relevance (85.6%). Conversely, Gemini 2.0 Flash demonstrated a trade-off: while it achieved reasonable accuracy (76.4%), its comprehensiveness (62.8%) was significantly lower than that of the LRMs (P < 0.05), reflecting limitations in depth of elaboration despite factual correctness. ChatGPT-4o outperformed ChatGPT-4 across all evaluated dimensions but remained statistically inferior to Grok 3 (Think) in terms of accuracy (P < 0.001). Overall, Grok 3 (Think) emerged as the most balanced and consistently high-performing model, distinguished by its ability to generate accurate, contextually relevant, and well-articulated clinical responses.

4. Discussion

In the clinical management of radiation oncology, physicians frequently encounter complex scenarios shaped by numerous individual and contextual factors. Informed decision-making requires not only deep medical expertise, which is continuously evolving with new therapies and clinical trial data, but also the ability to assess nuanced trade-offs between risks and benefits. While large language models have demonstrated promising performance in medical examinations [15, 16], these assessments, typically based on multiple-choice formats with definitive answers, fail to fully capture the uncertainty and complexity inherent in real-world clinical practice [17]. Moreover, reliance on publicly available training data introduces the risk of data contamination, potentially inflating perceived model performance. To address these issues, the present study employed a novel set of open-ended clinical management questions that closely mimic real-world scenarios where radiation oncologists might seek AI-based support, with a multi-dimensional scoring system for comprehensive performance evaluation.

ChatGPT-4 was among the most extensively studied generative AI models in radiation oncology. Huang et al. [18] noted its capacity to generate personalized treatment plans, occasionally offering novel insights not previously considered by clinicians. However, its tendency to produce "hallucinations" necessitates caution. Similarly, Ramadan et al. [7] found that ChatGPT-4 performed well in factual recall but struggles with higher-order clinical decision-making, particularly in areas, such as toxicity management and treatment planning, limitations likely stemming from its restricted reasoning capabilities.

Our findings corroborated these limitations. In the Staging module, ChatGPT-4 repeatedly misdefined TNM classifications under the AJCC 8th edition, such as incorrectly describing N1 as a "single ipsilateral lymph node, 3 cm or less." In the multidisciplinary treatment module, it inappropriately recommended induction chemotherapy for early-stage NPC and mischaracterized TP and PF regimens as standard induction protocols. While GPT-4o showed marginal improvement over GPT-4 (P = 0.047), similar inaccuracies persisted. Gemini 2.0 Flash performed comparably to GPT-4 (P = 1.00) but frequently offered vague or evasive answers. For instance, it declined to provide direct responses to two radiotherapy-related questions, consistent with earlier findings [19]. Echoing previous analogies, ChatGPT resembled an enthusiastic but inexperienced trainee [20], while Gemini presented as a more cautious counterpart. Notably, 87.0% of inferior responses in this study originated from LLMs, and their higher coefficient of variation (23.77%-24.50%) suggested inconsistency, making them less reliable in time-sensitive clinical settings lacking expert oversight.

The advent of large reasoning models showed a paradigm shift in AI development, comparable in impact to the original emergence of ChatGPT [21]. By embedding advanced reasoning mechanisms into LLM architectures, LRMs enable stepwise, context-aware deliberation that better reflected human cognitive processing. In oncology, this allowed for improved judgment in ambiguous or high-stakes scenarios. Our results confirmed that Grok 3 (Think) significantly outperformed other models, particularly in radiotherapy and multidisciplinary treatment modules, domains that require probabilistic reasoning and real-time trade-off analysis. Moreover, LRMs demonstrated more consistent performance, with lower coefficients of variation (Grok 3: 9.98%; Deepseek-R1: 13.98%).

Nevertheless, LRMs were not immune to hallucinations [22]. For example, Grok 3 (Think) inaccurately recommended bevacizumab for NPC with liver metastases, contrary to NCCN guidelines. Deepseek-R1 fabricated definitions for radiotherapy target volumes and frequently cited nonexistent journal articles, issues also reported in other GenAI models [23]. These errors highlighted the need for vigilant oversight, particularly when users lack the expertise to critically assess AI-generated content. Another pervasive limitation across all models was their outdated knowledge. In the staging module, responses reflected the AJCC 8th edition, despite the release of the 9th edition in September 2024 [24]. Similarly, none of the models referenced a key study on GTV delineation published in February 2025 [25]. Because most current models rely on static, pre-trained data rather than real-time information retrieval, they are inherently disadvantaged in fast-evolving clinical fields like radiation oncology. Performance in the toxicity and multidisciplinary treatment modules was also suboptimal. No model achieved more than 50% superior responses in either area, suggesting limitations in reasoning depth or gaps in domain-specific training data. These shortcomings underscored the need for domain-adapted model development.

Radiation oncology’s complexity and specialized knowledge base call for tailored AI solutions. Incorporating structured clinical records, up-to-date guidelines, standardized terminology, and scientific literature into training datasets could significantly improve GenAI performance in this field [26-28]. Equally important was the ability to trace evidence. In clinical practice, treatment decisions were often based on high-level evidence, and transparent citation of such sources could enhance clinicians’ confidence in AI recommendations. Recent efforts, such as retrieval-augmented generation [29] and domain-specific knowledge graphs [30], aimed to improve evidence traceability. Addressing hallucinations remained a priority, with promising developments including hallucination detectors for automatic error identification and correction [31, 32]. Further exploration of hallucination patterns specific to radiation oncology was warranted.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic comparison of LLMs and LRMs in addressing open-ended clinical questions related to nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Key strengths of this study include a rigorously designed, 50-question, expert-curated evaluation set and a validated multi-dimensional scoring framework. Findings indicate that LRMs offer clear advantages in clinical reasoning, reliability, and performance consistency, supporting their potential integration into radiation oncology workflows. The limitations of this study included the use of single-session queries, which might not reflect the iterative, interactive nature of clinical consultations or account for response variability inherent to GenAI models. Additionally, the sample size, limited to 10 questions per module, restricted detailed subdomain analyses. Finally, the study did not include medical imaging inputs, despite their essential role in diagnosis and treatment planning in radiation oncology.

5. Conclusion

In this study, large reasoning models such as Grok 3 (Think) and Deepseek-R1 outperformed traditional large language models in addressing complex, open-ended clinical scenarios related to nasopharyngeal carcinoma. However, persistent limitations, including outdated knowledge, hallucinations, and limited evidence traceability, underscored the need for further refinement. With targeted training using domain-specific data, improved evidence citation mechanisms, and hallucination mitigation strategies, reasoning-enhanced GenAI has the potential to become a reliable clinical decision-support tool in radiation oncology. Future research will expand to include larger question sets, additional cancer types, multimodal data (e.g., imaging), and multi-turn dialogue to further validate and optimize the clinical utility of these advanced AI systems.

Data Sharing

This study did not include a data sharing plan, additional data from the study will not be shared publicly. The authors affirm that generative AI and AI-assisted technologies were used to support language editing and refinement during the preparation of this manuscript. All content was critically reviewed and verified by the authors to ensure accuracy, integrity, and adherence to academic standards. No AI tools were used for data analysis, interpretation of results, or drawing scientific conclusions.

Ethical Approval

This study does not include any individual-level data and thus does not require any ethical approval.

Funding

This study is supported by the China National Science Foundation (Grant numbers 62307031).

Competing Interests

None.

Author Contributions

Lihong Wang and Luxun Wu contributed equally to this work and share first authorship. Study conception and design: Danfang Yan, Senxiang Yan. Data collection: Lihong Wang, Luxun Wu, Feng Jiang. Data analysis and interpretation: Wenxiang Li, Yang Yang, Luxun Wu. Manuscript drafting: Lihong Wang, Luxun Wu. Critical revision of the manuscript: Danfang Yan, Senxiang Yan. Supervision and project administration: Danfang Yan, Senxiang Yan. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Guarantor

Danfang Yan, Ph.D.

Assuta Bariatric Surgeons Collaborative

REFERENCES

[1] IBM

“What is generative AI?”, 2023

[2] Bal Ram, Pratima Verma “Artificial

intelligence AI-based Chatbot study of ChatGPT, Google AI Bard and Baidu AI.” World

Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences, vol. 8, no. 1,

pp. 258-261, 2023. View at: Publisher Site

[3] Geoffrey W Rutledge “Diagnostic

accuracy of GPT-4 on common clinical scenarios and challenging cases.” Learn

Health Syst, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. e10438, 2024. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[4] Emile B Gordon, Alexander J Towbin,

Peter Wingrove, et al. “Enhancing Patient Communication With Chat-GPT in

Radiology: Evaluating the Efficacy and Readability of Answers to Common

Imaging-Related Questions.” J Am Coll Radiol, vol. 21, no. 2, pp.

353-359, 2024. View at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[5] Yat-Fung Shea, Cynthia Min Yao Lee,

Whitney Chin Tung Ip, et al. “Use of GPT-4 to analyze medical records of

patients with extensive investigations and delayed diagnosis.’ JAMA Network

Open, vol. 6, no. 8, pp. e2325000, 2023. View at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[6] Ethan Goh, Robert J Gallo, Eric

Strong, et al. “GPT-4 assistance for improvement of physician performance on

patient care tasks: a randomized controlled trial.” Nat Med, vol. 31,

no. 4, pp. 1233-1238, 2025. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[7] Sherif Ramadan, Adam Mutsaers,

Po-Hsuan Cameron Chen, et al. “Evaluating ChatGPT’s competency in radiation

oncology: A comprehensive assessment across clinical scenarios.” Radiother

Oncol, vol. 202, pp. 110645, 2025. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[8] Kylie Robison, “OpenAI releases

GPT-4o, a faster model that’s free for all ChatGPT users.” 2024.

[9] Koray Kavukcuoglu “Gemini 2.0 is now

available to everyone.” 2025.

[10] Daya Guo, Dejian Yang, Haowei Zhang,

et al. “Deepseek-r1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in llms via

reinforcement learning.” arXiv, pp. 2501.12948, 2025. View at: Publisher Site

[11] xAI, “Grok 3 Beta-The Age of

Reasoning Agents.” 2025.

[12] Xueyang Zhou, Guiyao Tie, Guowen

Zhang, et al. “Large Reasoning Models in Agent Scenarios: Exploring the

Necessity of Reasoning Capabilities.” arXiv, pp. 2503.11074, 2025. View

at: Publisher Site

[13] Fengli Xu, Qianyue Hao, Zefang Zong,

et al. “Towards Large Reasoning Models: A Survey of Reinforced Reasoning with

Large Language Models.” arXiv, pp. 2501.09686, 2025. View at: Publisher Site

[14] Yu-Pei Chen, Anthony T C Chan,

Quynh-Thu Le, et al. “Nasopharyngeal carcinoma.” Lancet, vol. 394, no.

10192, pp. 64-80, 2019. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[15] Aidan Gilson, Conrad W Safranek,

Thomas Huang, et al. “How Does ChatGPT Perform on the United States Medical

Licensing Examination? The Implications of Large Language Models for Medical

Education and Knowledge Assessment.” JMIR Med Educ, vol. 9, pp. e45312,

2023. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[16] Hui Zong, Rongrong Wu, Jiaxue Cha, et

al. “Large Language Models in Worldwide Medical Exams: Platform Development and

Comprehensive Analysis.” J Med Internet Res, vol. 26, pp. e66114, 2024.

View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[17] Catrin Sohrabi, Ginimol Mathew,

Nicola Maria, et al. “The SCARE 2023 guideline: updating consensus Surgical

CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines.” Int J Surg, vol. 109, no. 5, pp.

1136-1140, 2023. View at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[18] Yixing Huang, Ahmed Gomaa, Sabine

Semrau, et al. “Benchmarking ChatGPT-4 on a radiation oncology in-training exam

and Red Journal Gray Zone cases: potentials and challenges for ai-assisted

medical education and decision making in radiation oncology.” Front Oncol,

vol. 13, pp. 1265024, 2023. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[19] Kostis Giannakopoulos, Argyro

Kavadella, Anas Aaqel Salim, et al. “Evaluation of the Performance of

Generative AI Large Language Models ChatGPT, Google Bard, and Microsoft Bing

Chat in Supporting Evidence-Based Dentistry: Comparative Mixed Methods Study.” J

Med Internet Res, vol. 25, pp. e51580, 2023. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[20] Behzad Ebrahimi, Andrew Howard, David

J Carlson, et al. “ChatGPT: Can a Natural Language Processing Tool Be Trusted

for Radiation Oncology Use?” Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, vol. 116, no.

5, pp. 977-983, 2023. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[21] Maciej Besta, Julia Barth, Eric

Schreiber, et al. “Reasoning Language Models: A Blueprint.” arXiv, pp.

2501.11223, 2025. View at: Publisher

Site

[22] Abhika Mishra, Akari Asai, Vidhisha

Balachandran, et al. “Fine-grained Hallucination Detection and Editing for

Language Models.” arXiv, pp. 2401.06855, 2024. View at: Publisher Site

[23] Kostis Giannakopoulos, Argyro

Kavadella, Anas Aaqel Salim, et al. “Evaluation of the Performance of

Generative AI Large Language Models ChatGPT, Google Bard, and Microsoft Bing

Chat in Supporting Evidence-Based Dentistry: Comparative Mixed Methods Study.” J

Med Internet Res, vol. 25, pp. e51580, 2023. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[24] Jian-Ji Pan, Hai-Qiang Mai, Wai Tong

Ng, et al. “Ninth Version of the AJCC and UICC Nasopharyngeal Cancer TNM

Staging Classification.” JAMA Oncol, vol. 10, no. 12, pp. 1627-1635,

2024. View at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[25] Ling-Long Tang, Lin Chen, Gui-Qiong

Xu, et al. “Reduced-volume radiotherapy versus conventional-volume radiotherapy

after induction chemotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: An open-label,

noninferiority, multicenter, randomized phase 3 trial.” CA Cancer J Clin,

vol. 75, no. 3, pp. 203-215, 2025. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[26] Fujian Jia, Xin Liu, Lixi Deng, et

al. “OncoGPT: A Medical Conversational Model Tailored with Oncology Domain

Expertise on a Large Language Model Meta-AI (LLaMA).”

[27] Michael Moor, Oishi Banerjee, Zahra

Shakeri Hossein Abad, et al. “Foundation models for generalist medical

artificial intelligence.” Nature, vol. 616, no. 7956, pp. 259-265, 2023.

View at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[28] Cyril Zakka, Rohan Shad, Akash

Chaurasia, et al. “Almanac - Retrieval-Augmented Language Models for Clinical

Medicine.” NEJM AI, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 10.1056/aioa2300068, 2024. View

at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[29] Yu Hou, Jeffrey R Bishop, Hongfang

Liu, et al. “Improving Dietary Supplement Information Retrieval: Development of

a Retrieval-Augmented Generation System With Large Language Models.” J Med

Internet Res, vol. 27, pp. e67677, 2025. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[30] Xiaona Liu, Qing Wang, Minghao Zhou,

et al. “DrugFormer: Graph-Enhanced Language Model to Predict Drug Sensitivity.”

Adv Sci (Weinh), vol. 11, no. 40, pp. e2405861, 2024. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[31] Anne-Dominique Salamin, David Russo,

and Danièle Rueger “ChatGPT, an excellent liar: How conversational agent

hallucinations impact learning and teaching.” Proceedings of the 7th

International Conference on Teaching, Learning and Education, 2023.

[32] Abhika Mishra, Akari Asai, Vidhisha Balachandran, et al. “Fine-grained Hallucination Detection and Editing for Language Models.” arXiv, pp. 2401.06855, 2024. View at: Publisher Site